Opinion

Oil Revenue Management And Economic Performance In Nigeria: Goodluck Jonathan’s Era In Comparative Perspective

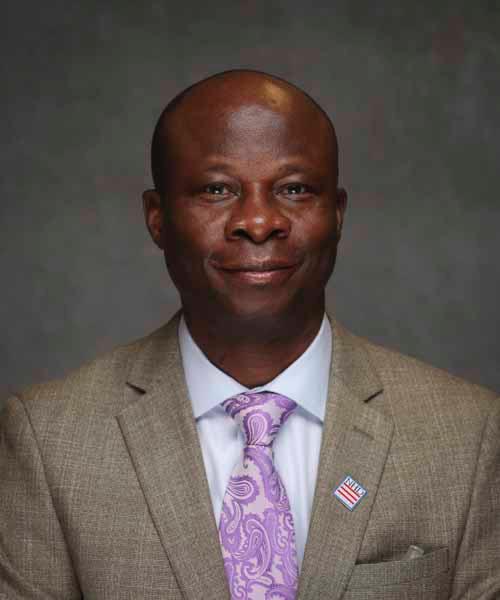

Bukola Adeyemi Oyeniyi (Ph.D.)

Reynolds College, Missouri State University

Email:BukolaOyeniyi@missouristate.edu

Introduction

Nigeria’s economic fortunes have long been tied to crude oil. As Africa’s top oil producer, petroleum exports historically contribute about 95% of Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings and the bulk of government revenue. How successive administrations manage this oil wealth – whether by saving for the future or squandering revenues – has far-reaching implications for economic stability. In this essay, I investigate and evaluate the management of crude oil revenue under President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan (2010–2015), comparing his administration’s performance to those of Presidents Olusegun Obasanjo (1999–2007) and Muhammadu Buhari (2015–2023). I also examine broader economic indicators such as GDP growth, inflation, foreign reserves, and public debt to provide context to the outcomes of each era.

This analysis draws on official data, audits, and reports to present a fact-driven account. It highlights how record oil revenues during Jonathan’s tenure coincided with missed opportunities for savings and corruption scandals, and contrasts this with Obasanjo’s more fiscally prudent approach and Buhari’s struggle with low oil prices and rising debt. In doing so, the essay traces the arc of Nigeria’s economy through oil booms and busts, and the policy choices that shaped Nigerians’ livelihoods.

The impetus for the essay is the recent revelation by Dr. Ngosi Okonjo-Iweala about the lack of political will that characterized President Ebele Jonathan’s leadership of Nigeria, most especially in relation to the oil windfall of his era and the lack of any significant economic and infrastructural progress that defined Jonathan’s rule.

Obasanjo Era (1999–2007): Laying a Fiscal Foundation during an Oil Boom

President Olusegun Obasanjo assumed office in 1999 as Nigeria returned to democracy, coinciding with the start of a 2000s commodities boom. Oil prices rose steadily during his tenure, especially in the mid-2000s, providing a windfall of petrodollars. Obasanjo’s administration is often credited with a relatively prudent management of this windfall in several ways:

Creation of the Excess Crude Account (ECA): In 2004, Obasanjo’s government established the ECA, a stabilization fund to save oil revenues above the annual budget benchmark price. This mechanism aimed to “protect planned budgets against shortfalls due to volatile crude oil prices”. With political will and cooperation between the federal and state governments, the ECA accumulated substantial savings during the boom. By 2007, Nigeria had saved roughly $22 billion in the ECA according to the then Finance Minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala. Okonjo-Iweala noted that “we saved $22 billion because the political will to do it was there”, which proved crucial when a downturn hit in 2008/09 – Nigeria was able to tap these reserves to stimulate the economy without seeking emergency loans. In fact, about $5 billion (≈5% of GDP) was injected from the ECA in 2009 to counter the global financial crisis, helping Nigeria avoid a recession.

Foreign Reserve Accumulation: Thanks to high oil earnings and prudent saving, external reserves surged from about $7 billion in 1999 to $43 billion by May 2007. This provided a healthy buffer for the balance of payments. Notably, September 2008 (shortly after Obasanjo left) saw reserves peak at $62 billion, the highest in Nigeria’s history, reflecting saved oil receipts. Obasanjo himself later claimed he left $25–35 billion in ECA and a large reserve, though official records clarify that the $43 billion gross reserves in 2007 comprised $31.5 billion in Central Bank reserves and $9.43 billion in the ECA. Regardless of exact figures, the trend is clear: the Obasanjo administration leveraged the oil boom to build fiscal buffers.

Debt Relief and Fiscal Reform: A hallmark of Obasanjo’s tenure was negotiating debt relief in 2005. Nigeria paid off $12 billion and had about $18 billion forgiven, eliminating its Paris Club debt. This slashed public debt from roughly 60% of GDP in 1999 to just 7% of GDP by 2007. By leaving a low debt burden, Obasanjo freed up future oil revenues for development rather than debt service. His government also introduced reforms like oil sector transparency (joining the EITI initiative) and anti-corruption agencies (EFCC, ICPC) to curb graft, though enforcement was mixed. Notably, revenue as a share of GDP slightly declined from 7.3% to 6.1% under Obasanjo, reflecting that despite high oil income, government revenue collection did not grow as fast as the economy – a sign of Nigeria’s narrow tax base.

Exchange Rate and Inflation: The Obasanjo years saw major exchange rate adjustments – the naira moved from ₦21 per US$1 in 1999 to about ₦128 per US$1 by 2007. This large devaluation unified rates and reflected inflation differentials. Inflation, which was high in the late 1990s, was brought down from ~12% to ~8.5% by 2007. Tighter monetary policy and improved food supply helped achieve single-digit inflation by the end of Obasanjo’s term, laying groundwork for stability.

Economic Growth: With reforms (e.g. banking consolidation, telecoms liberalization) and rising oil output, Nigeria’s GDP growth averaged nearly 7% annually under Obasanjo. The economy expanded from about $37 billion in 1999 to over $166 billion by 2007 (in nominal terms), and annual growth accelerated to 6–8% by the mid-2000s. Unemployment edged up slightly (10% to 12%), but there were significant job gains in sectors like telecom and services following deregulation.

Obasanjo’s tenure was not without controversy – allegations of corruption in the oil sector (such as the Halliburton bribery scandal and opaque allocation of oil blocks) did surface. However, the consensus is that Obasanjo left Nigeria in 2007 with robust economic fundamentals: large savings, low debt, and a growing economy. In later years, Obasanjo would criticize his successors for squandering these gains. He pointed out that “Almost $25 billion we kept in excess crude [account]…for the rainy days…[was] raised to $35 billion when we left office in May [2007].” He lamented that this cushion was depleted by subsequent administrations. Indeed, analysis shows the ECA rose from $5.1 billion in 2005 to over $20 billion by 2008, then fell to under $4 billion by 2010. The stage was set for Goodluck Jonathan, who as Vice President under Umaru Musa Yar’Adua (2007–2010) and then President, would preside over another oil boom – with far less fiscal restraint.

Goodluck Jonathan’s Presidency (2010–2015): Oil Boom, Corruption, and Missed Opportunities

Goodluck Jonathan inherited a nation benefitting from a rebound in oil prices after the 2008–2009 slump. Between 2010 and 2014, global oil prices stayed mostly above $80 per barrel, even exceeding $100 for extended periods. This translated into record export revenues for Nigeria. Under Jonathan:

Record Oil Revenues: Nigeria’s oil exports hit all-time highs in the early 2010s. In 2011, 2012, and 2013, export earnings were $99.8 billion, $96.9 billion, and $97.8 billion respectively – the highest in Nigeria’s history. By comparison, exports were about $80 billion in 2010 and plunged to $34.7 billion by 2015. This boom was driven by steady production (~2.3 million barrels per day) and high prices. According to the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), Nigeria earned $68.4 billion from oil and gas in 2011, and $62.9 billion in 2012. For context, the 2012 oil revenue of ₦12.5 trillion (≈$63 billion) accounted for the vast majority of government income. Such windfalls provided a historic opportunity to invest in infrastructure, save for future downturns, and diversify the economy.

Minimal Savings and ECA Depletion: Despite these record inflows, Jonathan’s government saved very little. The Excess Crude Account, which had about $4 billion in 2010, saw some deposits during the boom but was rapidly drawn down. By December 2012, the ECA reached $9 billion, but by early 2015 it had plummeted to only $2.5 billion. In other words, over $6 billion from the oil savings account was drained during a period of high oil prices with little to show for it. Nigeria entered 2015 – just as oil prices collapsed – with virtually no fiscal cushion. Then-Finance Minister Okonjo-Iweala candidly admitted that there was “no political will to save” oil revenue under Jonathan, blaming pressure from powerful state governors who insisted on sharing the funds. Indeed, state governors (led by Rotimi Amaechi at the time) argued that the ECA was opaque and kept “dropping” without explanation, so they fought for the money to be distributed rather than parked in Abuja. President Jonathan often yielded to these demands, authorizing withdrawals that left the account bare. By 2013, allegations arose that $5 billion was “missing” from the ECA and $2 billion withdrawn without authorization, highlighting grave transparency issues. The Nigerian Senate later described the ECA as “one of the most poorly managed” funds in the world, an avenue for “revenue leakages”. Till date, President Jonathan is yet to account for this huge amount of money.

Sovereign Wealth Fund Attempt: To institutionalize savings, Jonathan’s administration in 2011 established the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) with a $1 billion seed (Nigeria’s first sovereign wealth fund). The NSIA was structured into a stabilization fund, infrastructure fund, and future generations fund. However, due to opposition from governors (who saw it as usurping the ECA) and continuous fiscal pressures, the SWF remained small. By 2015, the NSIA had only around $1–$1.5 billion under management – a tiny fraction of oil earnings. The intent was sound (Norway-style investment of oil surplus), but the political consensus to consistently fund the SWF was lacking, undermining its impact.

Fuel Subsidy Scandal (“Oil Subsidy Scam”): A defining controversy of Jonathan’s tenure was the uncovering of massive corruption in the petroleum subsidy program. Nigeria has long subsidized fuel, but costs exploded under Jonathan. A parliamentary probe in 2012 revealed that between 2009 and 2011 the fuel subsidy scheme was “fraught with endemic corruption and entrenched inefficiency”. During that period, importers were paid for 59 million liters of gasoline daily while Nigerians only consumed about 35 million liters – indicating huge ghost shipments. The House of Representatives report found ₦2.587 trillion (about $16.46 billion) was spent on subsidies in 2011 alone, an overspend of over 900% on the ₦245 billion budgeted. This excess equaled over half of the entire federal budget in 2011, effectively siphoning public funds to private pockets. In total, an estimated $6.8 billion was defrauded over 2009–2011 via subsidy scams – about a quarter of Nigeria’s annual budget in that period. The state oil company NNPC was implicated: it was found to owe the government ₦704 billion for subsidy violations and owed fuel traders $3.5 billion – ironically “about the amount in the Excess Crude Account, meaning that Nigeria essentially has no savings”. The rot included dozens of bogus fuel import companies (140 firms in 2011 up from 5 in 2006) claiming subsidies on fuel that was never delivered. One egregious example: in just 24 hours in January 2009, the Accountant-General’s office made 128 subsidy payments of ₦999 million each (just under ₦128 billion total) in a frantic binge. This scandal, when exposed, led to nationwide protests in January 2012 (the “Occupy Nigeria” movement) after Jonathan attempted to remove the subsidy.

The public outrage forced the government to backtrack partially and prosecute a few culprits, but the episode underscored how badly oil revenues were mismanaged under President Jonathan. A Reuters report observed that NNPC operated with little accountability, essentially “a state within a state” during this time. Jonathan’s reluctance to punish top officials (many implicated were his political allies) undermined his anti-corruption stance.

“Missing $20 Billion” NNPC Controversy: Another headline event was the claim by the Central Bank Governor, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, in late 2013 that the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) had failed to remit $20 billion in oil revenues to the treasury. Sanusi’s letter to President Jonathan (leaked to the press) alleged huge “leakages” at NNPC during 2012–2013. He initially cited up to $49 billion missing, then revised it to $20 billion upon further reconciliation. Sanusi did not claim the money was outright stolen, but documented systemic subversions – unapproved spending, opaque accounting for crude sales, and strategic alliance agreements that shortchanged the nation. His dossier ran over 300 pages, detailing “waste, mismanagement and…‘leakages’ of cash in Nigeria’s oil industry”. For example, NNPC was accused of diverting crude oil proceeds to pay for unaudited kerosene subsidies and sweetheart deals with traders, without depositing funds into the

Federation Account. Sanusi warned in his letter that if such leakages continued in an era of high oil prices, “the consequences for the economy would be disastrous”, noting that failing to save oil earnings was making exchange rate and price stability “extremely difficult”. He presciently wrote that the alternative to plugging leaks would be “a devalued currency… and financial instability”, and indeed that is what transpired. The government’s response was to deny wrongdoing; Jonathan publicly dismissed the claims and controversially suspended Sanusi in February 2014, accusing him of “financial recklessness” at the central bank instead. A Senate committee later could not account for about $700 million but generally downplayed Sanusi’s figures, and an external audit by PwC found unremitted funds of a smaller magnitude (around $1.5 billion). Still, the episode badly hurt the administration’s credibility and underscored longstanding NNPC opacity. By early 2015, as Sanusi had cautioned, Nigeria was reeling: oil prices plunged by 50%, the naira was devalued by ~8%, foreign reserves fell 20% year-on-year, and inflationary pressures mounted. In the words of Reuters, “Nigerian foreign exchange reserves [dropped] around 20%… while the balance in the country’s oil savings account [fell] from $9 billion in December 2012 to $2.5 billion at the start of [2015], even though oil prices were buoyant over much of that period”. The squandered opportunity became painfully evident.

Macroeconomic Outcomes: Despite these governance issues, the Jonathan years did see some positive economic indicators:

GDP Growth: Nigeria’s economy continued to grow robustly for most of Jonathan’s tenure. Real GDP growth averaged about 6.1% per year from 2010–2014, propelled by high oil income and growth in sectors like telecommunications, banking, and services. In April 2014, Nigeria rebased its GDP calculation, nearly doubling the estimated size of the economy. This statistical update revealed Nigeria as the largest economy in Africa with a GDP over $500 billion. By Jonathan’s last full year (2014), GDP growth was around 6.3%, though it sharply decelerated to about 2.3% in 2015 as oil revenues collapsed. Overall, Jonathan presided over an expanding economy – the GDP in USD terms grew by roughly 54% from 2010 to 2014, aided by both real growth and rebasing.

Inflation and Monetary Policy: Under Jonathan, inflation moderated from 14% in 2010 to about 8% by 2015, reaching its lowest level since the 2000s. The Central Bank under Sanusi (until 2014) maintained a tight monetary policy, holding interest rates high and managing the naira’s exchange rate within a band. This helped stabilize prices, and Nigeria experienced single-digit inflation for an extended period (2013–2015). The naira’s official exchange rate moved gradually from ~₦150/$ to ₦197/$ by 2015. However, this stability was partly artificial – sustained by reserve drawdowns and currency controls that became hard to maintain once oil earnings fell.

External Reserves: As noted, Jonathan’s term began with reserves of $37+ billion (mid-2010) and ended with around $28.3 billion in May 2015. In between, reserves fluctuated: they rose in early 2013 to ~$48 billion but were used heavily to defend the naira in 2014. The net decline of about $9 billion from 2010 to 2015 indicates that the high oil inflows were not conserved – they were either spent or lost to capital flight. By comparison, Obasanjo grew reserves by over $35 billion; Jonathan reduced them by roughly $9 billion.

Unemployment and Poverty: Official figures oddly showed unemployment falling to 6.4% by 2015 from ~19.7% in 2010. This drop is misleading; it reflects a change in methodology and the reclassification of many jobless people as “underemployed.” In reality, Nigeria’s job creation did not keep pace with its youthful population. Other indicators like poverty rates remained high. Critics like former World Bank VP Oby Ezekwesili noted that despite the oil boom, poverty worsened – by 2010 an estimated 112 million Nigerians were living in poverty, up from 68 million in 2004. “The more we earned from oil, the larger the population of poor citizens,” she observed, calling Nigeria “a paradox of wealth that breeds penury”.

In sum, President Jonathan’s era was characterized by unprecedented oil revenue – and equally unprecedented leakages and missed opportunities for reform. A damning assessment came from Ezekwesili in 2013, when she decried the “squandering of $45 billion in foreign reserves and another $22 billion in the Excess Crude Account” by the Yar’Adua-Jonathan administration, calling it “the most egregious” example of bad governance. She questioned: “Where did all that money go?… What exactly symbolises this level of brazen misappropriation of public resources?” Jonathan’s government did make some progress – for example, creating the Sovereign Wealth Fund, expanding infrastructure (new power projects, roads, revived rail lines), and agriculture reforms to cut food imports. However, these were overshadowed by rampant corruption in the oil sector and failure to institutionalize fiscal discipline. When the oil price crashed in late 2014, Nigeria was left highly vulnerable: the currency was devalued, government revenues plummeted, and by 2015 the nation slid toward economic crisis. This was the daunting situation inherited by Muhammadu Buhari in May 2015.

Buhari Era (2015–2023): Fighting Corruption Amid Economic Headwinds

Muhammadu Buhari came to power on a platform of anti-corruption and change, with many Nigerians believing he would steer the country differently from his predecessor. His timing was unfortunate – Buhari took office just as Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy was reeling from the oil price collapse (which saw crude drop from over $100 to below $50 per barrel by early 2015, and as low as $30 in early 2016). The challenges were manifold: fiscal crunch, a near-depleted ECA, rising public expectations, and ongoing insurgencies and militancy affecting oil production. Buhari’s administration responded with a mix of policies and experienced its own set of economic outcomes:

Anti-Corruption and Oil Sector Reforms: Buhari, a former military ruler known for personal austerity, initially took a hardline stance on corruption. His government pursued some high-profile corruption cases and instituted reforms like the Treasury Single Account (TSA) to centralize government revenues, aiming to plug leakages. In the oil sector, the long-delayed Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) was finally passed in 2021, restructuring NNPC into a limited liability corporation and aiming for more transparency. NNPC began publishing audited financial statements for the first time (from 2019 onwards), a noteworthy change in accountability. However, critics argue these measures yielded modest practical gains. Nigeria’s ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index saw no dramatic improvement, and corruption simply took new forms (for example, inflated contracts or continued oil theft at the upstream level). Buhari did appoint himself Petroleum Minister, with a trusted ally overseeing day-to-day operations, theoretically to exert control over NNPC. Yet, the state oil company still struggled with opacity – notably, under Buhari, NNPC claimed that fuel subsidy costs were consuming so much revenue that by 2022 it remitted zero oil proceeds to the federal treasury, a scenario that mirrored the past misuse albeit under a different justification.

Continuation of Fuel Subsidies: Ironically, the Buhari administration – which lambasted Jonathan’s handling of subsidies – continued and even expanded subsidy expenditures. In 2016, Buhari raised petrol prices and spoke of phase-out, but by 2017–2019, subsidies crept back as oil prices rose. Rather than a transparent budgeted subsidy, NNPC was simply covering the cost differentials (“under-recovery”) from its crude sales. An estimated ₦10 trillion was spent on fuel subsidies during Buhari’s tenure, especially in later years when oil prices climbed. This massive outlay drained resources that could have been invested elsewhere. Buhari repeatedly postponed final subsidy removal (fearing public backlash), leaving the tough decision to his successor in 2023. Thus, a key structural reform opportunity was largely missed until the end of his term.

Economic Recession and Recovery: Lacking the fiscal buffers that Obasanjo enjoyed, Nigeria entered a recession within a year of Buhari’s arrival. By Q2 2016, the economy contracted sharply – the first recession in 25 years. The causes were both external and internal: oil prices were low and militants in the Niger Delta, reacting to Jonathan’s electoral losses, resumed militancy that cut oil output to ~1.2 million barrels/day in 2016 (from 2.1mbpd), while policy inaction exacerbated the situation. Buhari was slow to appoint an economic team and delayed necessary responses. Observers noted that the absence of ministers for 6 months in 2015 and a delayed budget in 2016 hampered the response. Only by mid-2017 did Nigeria exit recession, as oil production and prices modestly recovered and the government launched an Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP). Growth under Buhari remained anemic though: 2016 saw -1.6% GDP growth, 2017 about 0.8%, and 2018–2019 around 1.9%. Another recession hit in 2020 due to COVID-19 (-1.9% for 2020). Over 2015–2022, Nigeria’s average annual GDP growth was only about 1.1% – the worst of any presidency since 1999. In effect, per capita income fell as population growth (2.6% p.a.) outpaced economic growth, worsening poverty. By 2022, over 60% of Nigerians lived in multidimensional poverty, a stark contrast to the high growth years before 2015.

Inflation and Exchange Rate: The Buhari era saw a return of high inflation and significant currency depreciation. Inflation spiked from 8% in 2015 to over 18% by 2016 following the naira devaluation and fuel price hikes. It remained in double-digits throughout Buhari’s term, reaching 22.4% by mid-2023. This surge was driven by currency weakness, food supply shocks, and expansive monetary/fiscal policy. On exchange rates, Buhari initially pegged the naira at ₦197/$, causing a severe forex shortage. By June 2016, the peg broke – the currency plunged, stabilizing around ₦305/$1 officially and ~₦500 on the parallel market. The Central Bank later introduced a multi-window system and by 2020 the official rate moved to ~₦360/$, but multiple devaluations saw it at ₦460/$ by 2023. In summary, the naira lost over half its value against the dollar during Buhari’s reign, reflecting weaker fundamentals. The wide gap between official and black-market rates (often 20-30% differential) also created rent-seeking opportunities and hindered investment.

Foreign Reserves and Capital Flows: Buhari’s administration managed to rebuild external reserves from the low point of 2015, aided by some recovery in oil prices and significant external borrowing. Reserves rose from $28.3 billion in May 2015 to about $45 billion in mid-2019, before sliding to ~$35 billion by 2023. The peak of $40+ billion in 2018–2019 was partly due to issuing Eurobonds and attracting foreign portfolio investors with high interest rates. However, Nigeria’s reserve gains under Buhari were fragile – they came from debt and “hot money” rather than accumulated savings from trade surpluses. Indeed, oil production challenges (the OPEC cap, vandalism, and theft that saw output fall to multi-decade lows in 2021/2022) meant Nigeria missed out on the full benefits of the late 2010s oil price uptick. By Buhari’s final year, surging global oil prices (near $100 in 2022) did not translate into significantly higher reserves or fiscal space, since Nigeria was importing refined fuel and paying subsidies, and oil output fell below 1 million barrels/day due to theft and underinvestment. A telling metric is the current account balance: it barely improved, moving from a small deficit of 0.2% of GDP in 2015 to 0.2% surplus by 2023. In short, the external sector remained weak.

Debt and Fiscal Balance: Facing revenue shortfalls, the Buhari government relied heavily on borrowing. The numbers are stark: Nigeria’s total public debt nearly doubled from ₦12.1 trillion in 2015 to about ₦41.6 trillion by 2022 (approx. $100 billion), and further to ₦77 trillion (~$170 billion) by mid-2023 when including Central Bank overdrafts. External debt in particular rose from a modest $7.3 billion in 2015 to $37 billion by 2023. Buhari effectively moved Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio from ~12% to ~23% – still moderate by international standards, but the real concern was debt service capacity. Government revenues did not keep up: oil production fell and non-oil revenues remained very low (tax collection was stagnant around 6-8% of GDP). As a result, the debt service-to-revenue ratio exploded from 29% in 2015 to roughly 96% by 2022, meaning nearly every naira earned went to creditors. This is an unsustainable fiscal situation.

Much of the deficit was financed by domestic borrowing and Central Bank financing (the “Ways and Means” advances). The CBN lent over ₦20 trillion to the government, basically printing money. The outcome was high inflation and a crowding-out of private sector credit. By 2023, Nigeria’s fiscal crunch was severe: in addition to debt service, the massive fuel subsidy (over ₦4 trillion in 2022) gulped most of the government’s revenue, leaving little for capital investment or social services. Public investment remained low at ~3% of GDP or less, despite needs for infrastructure.

Broader Economic and Social Indicators: Under Buhari, unemployment soared to 33.3% (by Q4 2020) from about 10% in 2015 – a reflection of two recessions and population growth outstripping job creation. Youth unemployment was even higher. The poverty headcount rose, making Nigeria the country with the most people in extreme poverty (as of 2018, according to World Bank indices). Manufacturing and FDI stagnated due to forex shortages and policy uncertainty. One slight positive was an increase in non-oil revenue contribution: the share of non-oil to total revenues grew from 45% in 2015 to 59% by 2022. However, this was less due to successful diversification and more because oil revenues shrank – in absolute terms, non-oil revenue growth was marginal. The agricultural sector saw attention (Buhari’s Anchor Borrowers’ Programme gave farmers loans), but results were mixed and marred by repayment issues. Infrastructure spending did increase nominally (the government invested in railways and highways, e.g. Abuja-Kaduna rail, Lagos-Ibadan Expressway), often funded by Chinese loans or borrowing. Nonetheless, the impact on GDP growth was limited by inefficiencies and the scale of needs.

In assessing Buhari’s legacy versus Jonathan’s, it is clear each faced distinct circumstances. Jonathan enjoyed boom times but failed to institutionalize savings or curb corruption, which left Nigeria exposed. Buhari faced bust times and emphasized anti-graft and austerity, yet economic outcomes were underwhelming – growth was negligible, inflation high, and debt piled up. Buhari did somewhat restore the image of personal integrity in leadership, but systemic change in oil revenue management was limited. For instance, while obvious embezzlement like the 2011 subsidy scam was not repeated at that scale, Nigeria still hemorrhaged billions through inefficiencies (e.g. the continuation of subsidizing fuel and losses from crude oil theft estimated at $2-3 billion annually in 2021/22). By 2023, Nigeria’s ECA balance was nearly zero and the Sovereign Wealth Fund remained around $3-5 billion – barely a drop compared to trillions earned over decades.

Comparative Analysis and Conclusion

Examining the three administrations side by side reveals patterns and critical differences in managing Nigeria’s oil wealth and economy:

Saving for a Rainy Day: Obasanjo’s tenure stands out for building savings (ECA and reserves). Jonathan’s tenure, despite higher oil earnings, depleted savings and left Nigeria with a very slim cushion – a fact that exacerbated the crisis of 2015–2016. Buhari, starting with almost no savings, was unable to rebuild them significantly; by the end of his term, reserves were only a few billion higher than when he started (from $28 billion to $35 billion), and the ECA was effectively empty. In essence, Nigeria squandered the boom revenues of the 2000s and early 2010s, and entered a period of lean revenue with little or no fiscal buffer.

Oil Revenue Transparency and Leakages: All three administrations struggled with transparency at NNPC, but Jonathan’s era was arguably the worst affected by outright scandals (the subsidy fraud, unremitted $20bn claim). Obasanjo had his share of corruption issues but also empowered institutions like the EITI audit and somewhat respected the idea of the ECA. Buhari improved transparency slightly (publishing NNPC accounts, passing PIB) but still couldn’t prevent huge “leakages” in the form of continuing subsidies and inefficiencies. Notably, under Jonathan corruption was more about misuse of excess funds during boom, while under Buhari it was about managing scarcity – yet even in scarcity, wasteful practices like subsidies and extra-budgetary spending persisted.

Economic Growth and Diversification: Obasanjo and Jonathan presided over high growth, buoyed by oil and some reforms (average ~7% and 6% respectively). Buhari’s Nigeria barely grew (~1% avg.), suffering recessions and slow recovery. None of the administrations achieved meaningful economic diversification – oil still dominates exports (~90%) and is a major share of government revenue (over 50%). However, some sectoral shifts occurred: Obasanjo’s era saw telecoms and banking rise; Jonathan’s saw the Nollywood and services become recognized in GDP; Buhari’s saw agriculture get policy focus. Yet, as of 2023, Nigeria remained vulnerable to oil price shocks, with non-oil tax to GDP around a paltry 4%, indicating that sustainable development remains elusive.

Inflation and Monetary Stability: Jonathan’s era can be credited for relatively low inflation (helped by a stable naira policy and recourse to fuel subsidies to cap energy prices), whereas Obasanjo’s era started with high inflation but ended low. Buhari’s era saw a return to high inflation, partly due to currency depreciation and monetization of fiscal deficits. Exchange rate wise, the naira depreciated in all three regimes, but most steeply in Buhari’s. By 2023, the naira’s value and Nigeria’s inflation were at their worst levels since the 1990s, reflecting macroeconomic misalignments.

Public Debt and Resilience: Obasanjo’s legacy was freeing Nigeria from the debt trap (debt/GDP fell to 7%). Jonathan’s government began accumulating debt again, but debt remained modest (debt/GDP ~12% by 2015). Under Buhari, debt exploded (debt/GDP ~23% by 2023, and nearly 35% if CBN overdrafts are included). The fiscal space created by Obasanjo was completely eroded, leaving Nigeria back in a precarious debt situation. This highlights how the management of oil revenue – whether used to pay down debt or to finance deficits – significantly altered Nigeria’s financial resilience.

In conclusion, the Goodluck Jonathan administration sat at the crest of an oil boom but largely failed to convert that into lasting blessings for Nigeria. Massive oil revenues translated into only short-term growth, while institutionalizing corruption and fiscal recklessness that left the economy exposed. Comparatively, Obasanjo’s administration, though not flawless, took steps to save oil windfalls and reduce debt, giving Nigeria a foundation that, had it been built upon, could have led to greater stability. The Buhari administration, inheriting an empty treasury and low oil prices, focused on fighting graft and managing crises, but ended up with high debt, high inflation, and low growth – effectively undoing many of the economic gains of the 2000–2014 period.

For Nigeria, these experiences underscore critical lessons. Diversifying the economy and depoliticizing the handling of oil revenues are essential. Windfalls must be saved or invested transparently, rather than fueling patronage. As one senator quipped about the Excess Crude Account, it became merely “an avenue for…leakages” – symptomatic of a larger governance problem. The human cost is evident in the persistently high poverty and unemployment despite decades of oil riches. The task for current and future leaders is to break this cycle. Nigeria’s recent moves – passing the Petroleum Industry Act, removing fuel subsidies (finally in 2023), and aiming to boost non-oil revenues – are steps that draw on the hard lessons from Jonathan’s time and others.

Ultimately, the Jonathan era will be remembered as a time of great opportunity for Nigeria, much of which was wasted through poor management of oil wealth. As one detailed investigative report lamented, Nigeria in those years exhibited a “comprehensive study of waste, mismanagement and…‘leakages’ of cash in [the] oil industry”. Comparing across administrations reveals that progress in governance has been halting and nonlinear. Only with consistent political will – of the sort briefly seen in the mid-2000s – can Nigeria hope to harness its oil endowment to truly benefit its economy and citizens, rather than enrich a few at the expense of many.

References

Daily Trust. (2023, June 4). How economy fared under Obasanjo, Yar’adua, Jonathan, Buhari.

Reuters. (2012, May 13). Factbox: Nigeria’s $6.8 billion fuel subsidy scam.

Reuters. (2015, Feb 6). Special Report: Anatomy of Nigeria’s $20 billion “leak”.

Premium Times. (2015, April 7). Nigeria earned N12.5 trillion as oil revenue in 2012 – NEITI.

TheCable. (2017, Dec 13). Fact Check: Did Obasanjo leave $65bn in excess crude account?.

African Liberty (via ThisDay). (2013, Jan 26). Oby Ezekwesili: Yar’Adua, Jonathan squandered $67bn in four years.

Nairametrics. (2022, July 1). How the Nigerian economy has performed under each President from 1999.

BudgIT. (2023, May). The Economic Legacy of the Buhari Administration.

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoFIRAT Offers USD 200,000 SnapGenius Research Facility To Boost Research Excellence In African Universities

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPolice Commence Investigation As Worshiper Mobbed To Death At Osogbo Central Mosque

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPensioners Threaten Legal Action Against States Over Unpaid Pension Increases, Outstanding Entitlements

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoAPC Obokun Feud : FAS Sues For Peace, Urges Party Members To Embrace Dialogue